My JS13k 2025 entry for the theme "Black Cat" is the game Witch Potion.

![]() It's a minimalistic, dialogue choice driven game about becoming a witch and mixing potions. As always, I used this competition as a tool to explore some things I had been wondering lately.

It's a minimalistic, dialogue choice driven game about becoming a witch and mixing potions. As always, I used this competition as a tool to explore some things I had been wondering lately.

Specifically, this year I had a few themes I wanted to incorporate.

- Mobile + Desktop

- Avoid canvas: use DOM

- Incorporate story!

- Limit Artwork

All my previous entries only worked on desktop due to ui and/or control incompatibility. Can I make something that works on both?

Every year I see lots of entries use the canvas api to do user interface. What kind of game could utilize the many features DOM api the best and still remain fairly small?

A certain difficulty of fitting a game in 13kb is that it has diminished space for important elements of a good story; things like proper exposition, detailed scenes, and characterization. Can I fit this in anyway?

Let the text do the talking. How much characterization can fit into emojis like 🐈⬛, 🐲, or 💀?

Did I accomplish these themes? Well, let's see...

The DOM and browser APIs

The browser has built into it a massive amount of features specifically for rendering sophisticated, modern, and customizable UI elements via the DOM, or Document Object Model. The browser supports a layout engine and stylization with css, it can capture events for all sorts of user input on a per element basis, and it can run transitions and animations with bare minimum boilerplate code. And those are the only things I really can think of right now It has a lot more interesting stuff potentially game-related stuff just built in right there, and it doesn't count towards your 13kb limit!

So why doesn't everybody use it in js13k?

If you look at the entries for this year (and previous years), you'll find lots of games that contain the simplest html file with a canvas inside of it, and they use immediate-mode rendering to render out their ui. No DOM, minimal CSS, and events are captured at the top level and handled with custom javascript. Some of these games feature minimal ui, and may not benefit from DOM usage, but others... I'm not so sure.

For example, if you want a minimalistic button with the DOM, you could create it with the createElement api:

const button = document.createElement('button');

Object.assign(button.style, {

width: '100px',

height: '32px',

});

button.innerHTML = 'My Button';

button.onclick = () => {

console.log('do something');

};

document.body.appendChild(button);

Fairly succinct, but perhaps more verbose boilerplate than I originally thought. What might this look like in a canvas api?

Well we have to think about a lot more things now than just the button and its styles.

- Event capturing requires mouse cursor location and collision detection.

- How is the button composed of primitives? How many rectangles, what text format?

- How is this button layed out like other buttons, and is it allowed to overlap?

- Does it have things like border, padding, or margin?

class Button {

constructor(x, y, width, height, text, options = {}) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

this.text = text;

this.borderColor = 'white';

this.lineWidth = 2;

this.font = 'Courier';

this.backgroundColor = 'gray';

}

draw(ctx) {

ctx.save();

const bgColor = this.isHovered ? this.hoverColor : this.backgroundColor;

ctx.fillStyle = bgColor;

ctx.fillRect(this.x, this.y, this.width, this.height);

ctx.strokeStyle = this.borderColor;

ctx.lineWidth = this.borderWidth;

ctx.strokeRect(this.x, this.y, this.width, this.height);

ctx.fillStyle = this.textColor;

ctx.font = this.font;

ctx.textAlign = 'center';

ctx.textBaseline = 'middle';

const textX = this.x + this.width / 2;

const textY = this.y + this.height / 2;

ctx.fillText(this.text, textX, textY);

ctx.restore();

}

isPointInside(mouseX, mouseY) {

return mouseX >= this.x &&

mouseX <= this.x + this.width &&

mouseY >= this.y &&

mouseY <= this.y + this.height;

}

handleMouseMove(mouseX, mouseY) {

this.isHovered = this.isPointInside(mouseX, mouseY);

}

handleMouseDown(mouseX, mouseY) {

if (this.isPointInside(mouseX, mouseY)) {

this.isPressed = true;

return true;

}

return false;

}

handleMouseUp(mouseX, mouseY) {

if (this.isPressed && this.isPointInside(mouseX, mouseY)) {

this.isPressed = false;

return true;

}

this.isPressed = false;

return false;

}

}

That's a lot bigger. Of course, that will minify down to considerably smaller at build time, but, it seems if you have a lot of distinct ui elements, this is going to take up more space than just using the DOM. However, this is only going to matter if the game your making requires a lot of ui. Genres like physics simulations and puzzle games might not need to care about the byte-impact of their ui elements. In this case the DOM is limited in usefulness. So then, in order to demonstrate the power of the browser, I needed a game that could take advantage of what it provides.

A Game that Leverages the DOM

What kind of game benefits from lots of ui elements? Considering the theme, I was thinking "board game" from the start, one with lots of events or pieces that could comprise the ui. I had recently played a board game called Escape the Dark Castle. It's a cooperative game where you and some friends play as medieval folks that try to escape an evil, Eldritch castle. Every round you draw a card with some horrifying art on it which has some kind of event that happens: you find a secret chest, some monster attacks you, a random cloud of suffocating dust kills half your party... The event card tells you what dice you have to roll and what you need to win, and you go until you die... or escape.

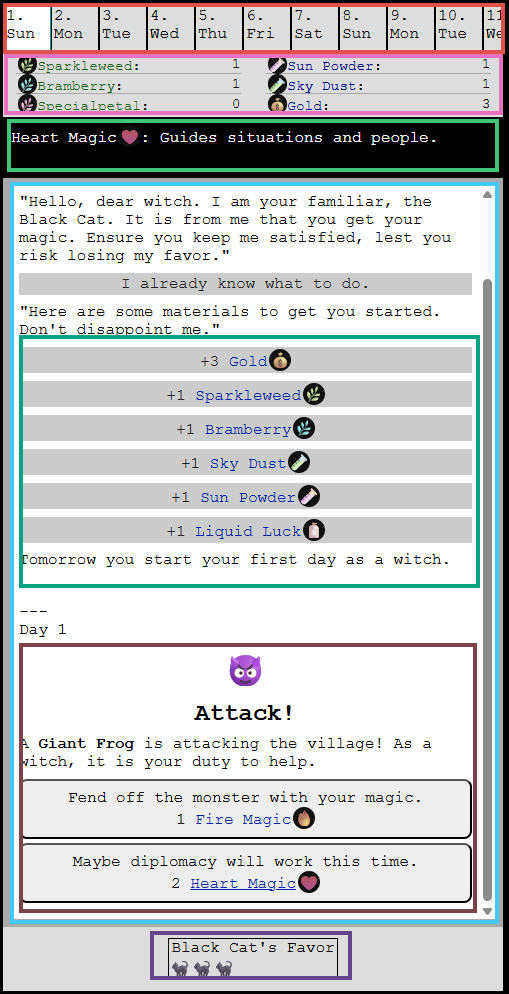

I thought this was a great base for the kind of game I wanted to make. A game like this requires a lot of ui elements: dice, icons, event descriptions, choices, lore, resources... And since it's a video game, it should leverage the ability to easily interact with all these things with clicks or taps. A good start, to be sure; I just had to fit the theme of Black Cat. I settled on the idea of the Black Cat being some kind of witch's familiar, and of course I've seen games like Potion Craft which aim to emulate a potion-crafter's life in a medieval town. It's a proven theme, so I thought it would be good to use. So, here's what I came up with.

That's a lot of complex ui! I shudder to think how much space that would take to write from scratch in a canvas. And that's to say nothing about the spinning dice or the way the events auto-scroll down smoothly:

Each of these ui elements are constructed via a simple function. This function returns a record of at least the root element, but also a reference to any important elements within the component. It uses the createElement api to construct a DIV, P, BUTTON, or SPAN depending on the need. There are some helper functions in there that wrap the DOM api so that there's less verbosity, but overall it's quite succinct.

Each component exists in its own file and exposes an api to modify it. For example the Calendar component has a function to advance the day, the Favor component allows you to add or subtract the cat's favor, the Dice element lets you spin it, and so forth. Since the constructor functions track the references to sub elements, it's easy to modify things like the dice face or the button text in the event ui. Obviously the most complex one is the event ui, which has to be flexible enough to show a bunch of distinct events, but also alow the Player to easily see what's going on. It takes an event object who's interface I'll describe later, and appends content to it based on a definition: like a card might, if you stacked them one on top of the other.

As for the spinning dice, that's achieved with a css animation and a timeout of the same length.

@keyframes spin {

from {

transform: rotate(0deg);

}

to {

transform: rotate(360deg);

}

}

export const diceSpin = (

dice: Dice,

resultValue: string,

ms: number,

rotations: number

) => {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setStyle(dice.root, {

animation: `spin ${ms / rotations}ms linear ${rotations}`,

});

diceSetFace(dice, DICE_DEFAULT_FACE);

setTimeout(() => {

setStyle(dice.root, {

animation: '',

});

diceSetFace(dice, resultValue);

resolve();

}, ms);

});

};

Scrolling smoothly also uses a native DOM api.

export const eventModalScrollToBottom = (eventModal: EventModal, smooth: boolean = true) => {

eventModal.content.scrollTo({

top: eventModal.content.scrollHeight,

behavior: smooth ? 'smooth' : 'auto',

});

};

I think I can conclude here that I was successful in my endeavor to make good use of the browser's built in apis. I don't think I could have made something of the same quality with base canvas within the 13kb limit.

Data Structure for Events

This idea is an event-based game about resource management, which relies on a back-and-forth with the Player.

- The game presents the Player with text describing something.

- The game gives the Player a set of choices.

- The Player makes a choice.

- The game responds to the choice and alters some resource or other data.

- Repeat.

Think of an Event as multiple sequences of the above strung together. A sequence is a child of an event. Enter the GameEventChild object, which stores all the information used to perform the above loop. Here's the simplest version of it.

export interface GameEventChild {

id: string;

p: string;

n: string;

}

- Each GameEventChild has an id so it can be identified by other events.

- The 'p' field indicates text which should be put in a P tag in html.

- The 'n' field is the id of the next GameEventChild to execute.

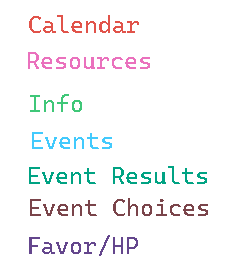

Simple, but useful. An example of this kind of event is right in the beginning of the game where the Black Cat informs you of the situation:

For something more interesting, the GameEventChild can be expanded to provide data for some choices.

export interface GameEventChoice {

text: string;

conditionText?: string;

n: string;

}

export interface GameEventChild {

id: string;

p: string;

choices: GameEventChoice[];

}

This data structure is starting to look a lot like a tree, one which the Player navigates to a desired outcome. The game can use this data to present a list of choices for what the next GameEventChild to execute should be. There's some additional functionality in there to disable this choice given some condition: the Player may only be able to make this choice if they have enough gold or meet some other condition.

So how do we include data to tell the game to do something when a choice is made? That depends on what we want to do. For a game like this, where the Player is managing resources, it is important for events to be able to modify any resource that the Player has. So, additional optional data can be stored here that represents a resource modification.

export interface GameEventChoice {

text: string;

conditionText?: string;

n: string;

}

export interface GameEventChild {

id: string;

p: string;

choices: GameEventChoice[];

mod?: string[];

}

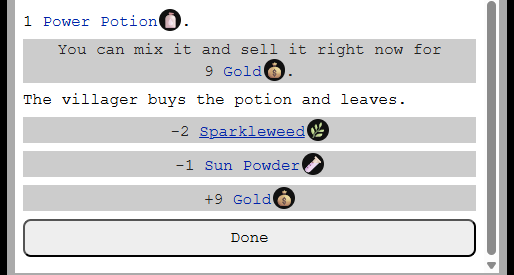

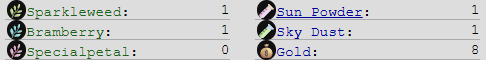

Each mod or modification string is encoded as a number and a resource: '2 GOLD', '3 SPARKLEWEED' etc. When a GameEventChild is run, the game can look at that mod list and alter the state of the game. For the Player, we see this as some deliberate text. It should be obvious what resources are added and removed each time this happens or you risk giving the Player lots of frustration:

The full data structure supports a few other bits and bobs, and is extendable as other features become necessary.

Writing Data

After deciding on a data structure, the next step is to create data to put in it! The problem is, the only way to do that right now is to write JSON by hand. Bleh.

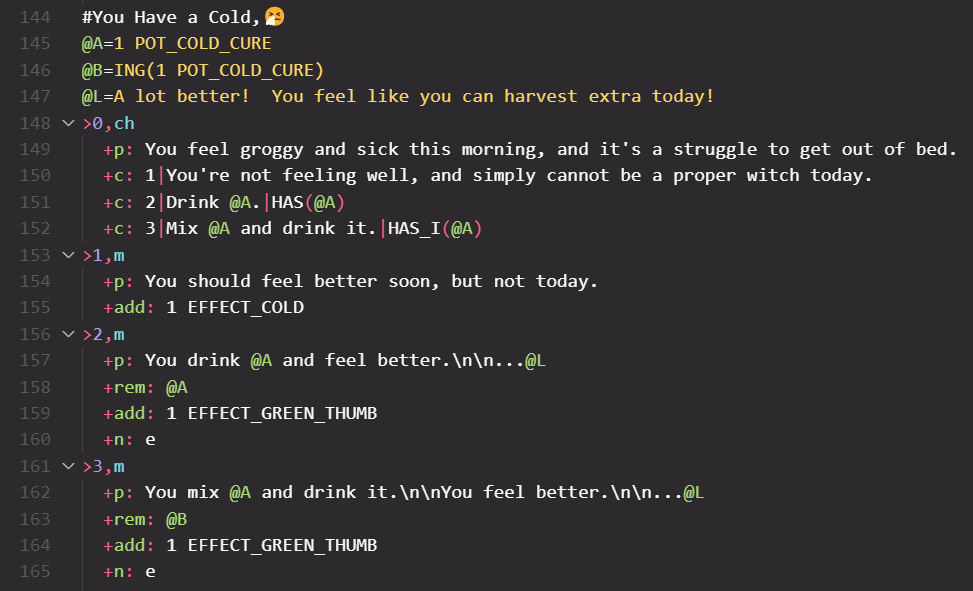

Instead, it would be nice if there was a syntax specifically for specifying these events which was easier to write. Then a parser could convert it to the underlying JSON which is then put in the game... And so that's how it works. This is an example of a "Witch Potion Event" file, or .wpe.

I ended up writing a VSCode plugin for syntax highlighting so that it was easier to visually parse. Events are prefixed with # and children with >. Individual components of an event child are prefixed with +. But the most important thing this syntax allows is variables.

Variables are prefixed by @ which are evaluated at runtime. Using variables can reduce string duplication to make the data footprint smaller, but that's a side effect of their real purpose. This allows the engine to run these events much more dynamically depending on the context.

Here's the Villager Contract event.

#Villager Contract,📜

@A=POT1(1)

@B=9 GOLD

@C=1 FAVOR_CAT

@D=ING(@A)

>0,ch

+m: @TEST

+p: A villager comes to your shop and requisitions a potion:\n\n@A.

+c: 1|Sell the potion for\n@B.|HAS(@A)

+c: 2|You can mix it and sell it right now for\n@B.|HAS_I(@A)

+c: 3|Say that you'll have the potion ready by next week.

>1,m

+p: The villager buys the potion and leaves.

+rem: @A

+add: @B

+n: e

>2,m

+p: The villager buys the potion and leaves.

+rem: @D

+add: @B

+n: e

>3,m

+p: The villager leaves, promising to return next week.

+n: e

+add: 1 CONTRACT_VILLAGER

The variable @A is assigned to a function which generates a random potion. For the rest of the event, this potion needs to remain consistent. So the engine evaluates the variable and stores it, then whenever it encounters @A in the children, it is replaced by the evaluated value. In this way, the same event can be re-used multiple times with different results.

With this new syntax I was able to fit in 17 distinct events. Honestly this is less than I had hoped, but still a reasonable number for a few playthroughs. During this process, I evaluated whether parsing this to json first then including it in the game, or bundling the game with the parser and the raw .wpe files, and concluded that the json was smaller. If there were longer variable names in the text then this result could be different.

Emoji Usage

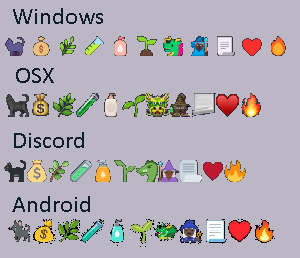

To save space this game uses emojis instead of custom svg icons for a little flair. 🐈⬛💰🌿🧪🧴🌱🐲🧙🏿♀️📃♥️🔥. There's a problem though, in that different operating systems/contexts render these all slightly differently.

For some reason, I did not know that before doing this project. TIL. They're all close enough that it doesn't matter all that much, but I did get comments about the "purple cat" instead of the black cat. To make them a bit more homogenous and give some alternate icons, a css 'filter' is applied to various icons. This can be seen in the resource area.

filter: hue-rotate(${degrees}deg);

...

filter: grayscale(75%);

Ludonarrative Harmony

When the idea of a potions shop started forming in my head, I had initially imagined a bunch of ingredients, mixing a bunch of complex potions that did all sorts of different things. Then selling these potions to villagers in a desperate attempt to get enough money to please the Black Cat. I ended up pairing that back quite a bit, but not just because I couldn't fit it in.

What's actually fun about potion making? Is it sort of like cooking where you combine a bunch of different ingredients in just the right way to make something delicious? It is similar, I think, but in this game we're missing the most important part: eating what you make.

In a game about potion making, the fun doesn't come from memorizing a whole bunch of arbitrary recipes and then NOT using the fantastic things you make. Potions are magical, they can do anything. In fact, the game should downplay memorization as much as possible so that players can pick up and play easily without a big headache!

So all these potions that the Player can make need to do something in the realm of the game mechanics. So what can they do?

I've already shown the mechanic of player choice in a sort of dialogue tree. The existence of a potion can easily affect such a tree. But there are other things potions can affect: things like spell casting.

By rolling dice, a Player casts spells. The type of spell they are intending to cast can be a fire 🔥, heart ♥️, or grow 🌱. A Player's dice starts as a 6-sided one with two edges each of these three types. When a dice is rolled, the face up indicates the magic that was actually disbursed. After the roll, count the number of your intended cast, and you've got the power level of a spell. Certain events require certain types and power levels for spells to pass, so it's in the Player's best interest to modify their dice in a way to reduce risk of casting spells.

With this mechanic, there are a whole bunch of effects potions can have: from modifying dice faces, to auto-rolling good results, to adding additional dice, to doubling up power... There are a lot of levers to tweak.

A good hint for this game is to use potions to reduce risk as much as possible, so that you can have a more consistent run. Things like Growth and Liquid Luck can all but guarantee passing an event, which in turn means more gold.

Closing Tips

I'll end this with a few closing tips about keeping a javascript game small.

- Concat before compilation

- Avoid all of this potential extra complexity in your code.

- One file allows you to minify variables at top level more easily.

- Reduce string duplication

If you use a tool like Vite or Webpack to build your game, you can likely save space by foregoing the build tool and simply concatenating all your source files together. These tools are capable of traversing a very complicated source tree to ensure your source is included in the right way. Your game's source tree is probably not all that complicated. Importantly, the way these tools bundle your code can create unnecessary overhead in a simple game that is meant to be under 13kb. If you got rid of all your import statements and concatenated all your files together in a single js file, you get two main benefits:

These combine to likely reduce your bundle size. However you must be mindful of this when writing the code: no default exports, and try to avoid running code unless it's inside of a function.

An example: if you find in your code multiple invocations of `document.createElement`, you can save space by wrapping that super long string in its own function. 20+ 'document.createElement', which cannot be minified, can be converted to

const createElement => (elemName) => document.createElement(elemName);

Each class you make translates to a javascript object. Unless you're careful to code in a way that you can mangle object properties, all of the functions you add to a class are going to take up extra space. You can mitigate this by separating your logic from your data and using a functional approach: create a blob of data that represents the context of your class, and use top level functions to modify it. For example, a silly class might look like this:

class MyObject {

someVariable = ''

constructor() {

this.someVariable = 'my variable';

}

setSomeVariable(a) {

this.someVariable = a;

}

}

const createMyObject = () => {

return { someVariable: 'my variable' };

}

const myObjectSetSomeVariable(obj, a) => {

obj.someVariable = a;

}

The folks who are good at js13k and win lots of prizes are really smart. They've probably thought of something you didn't in order to eek out more space for their projects. Look at their source code, figure out what they do, and see if you can incorporate it into your project.